Authorities made a series of questionable decisions in the hours before 17-year-old Cedric “CJ” Lofton stopped breathing at a Wichita juvenile intake center, according to an Eagle analysis of video footage and documents.

Now state and local officials vow to improve the system that failed Lofton, a foster child whose guardian had voiced concerns that his mental health was deteriorating.

“This situation is tragic, and we must find a way to ensure something like this never happens again,” Gov. Laura Kelly said in a written statement to The Eagle.

The Eagle analyzed video footage and reports by county corrections employees and the district attorney to identify critical turning points in authorities’ handling of the Black teen on the night he was taken into custody and fatally restrained.

The chain of events started when a caseworker told Lofton’s foster father to call police rather than let him in the house after he had been reported as a runaway.

Wichita police then detained the teen after trying to convince him to seek a mental health evaluation. When he became combative, they took him to a juvenile facility rather than a hospital.

There, corrections staff physically restrained Lofton in his cell for almost 45 minutes, according to video footage — approximately 10 minutes longer than the district attorney’s report noted. One employee who restrained him told police he applied weight to Lofton’s back.

At some point, Lofton went into cardiac arrest due to lack of oxygen. He died at Wesley hospital on Sept. 26, a day before he would have turned 18.

“This should never have happened,” District Attorney Marc Bennett said last week at a news conference where he announced he would not pursue charges against anyone involved in Lofton’s death.

Bennett said the county employees who restrained Lofton were immune from prosecution under Kansas’ “robust stand your ground law,” but his written report includes numerous policy recommendations for city, county and state agencies.

Meanwhile, Lofton’s family contends Bennett is the latest government official to fail the teen.

Steven Hart, a Chicago-based civil rights attorney representing Lofton’s biological family, called the decision not to pursue criminal charges “morally bankrupt.”

“This boy had committed no crimes,” Hart said. “He didn’t want to be there, and he was in a mental health crisis. Essentially what Marc Bennett is suggesting is, you did it to yourself, kid.”

Here are key turning points that night, based on documents and video.

Lofton’s foster father told investigators the teen walked away from school on the afternoon of Sept. 22. When he didn’t return home, his guardian reported him as a runaway.

Lofton returned to his east Wichita home on Sept. 23. His foster father drove him to Comcare for a mental evaluation, but the teen reportedly got out of the car and walked away.

When Lofton returned home at 1 a.m. the next day, his foster father first called his case worker at DCCCA, a private foster care agency that contracts with the Kansas Department for Children and Families, to report that Lofton was in mental distress.

According to Lofton’s foster father, the case worker told him to call police and not let Lofton in the house until after he had undergone a mental examination.

A representative for the foster agency told The Eagle that mental health crises are dealt with on a case-by-case basis and that DCCCA does not have a specific procedure for advising foster parents on how to handle a child in crisis.

“Foster care workers are 24/7, and so they respond if a kid is sick or if a kid is having behavioral issues or anything, so they’re there to guide a foster family through any sort of situation that may arise,” DCCCA spokesperson Alex Wiebel said.

“Whether the State of Kansas should accept a foster care system that responds to a foster father’s expression of concern that his foster son is in mental distress by telling the man, don’t let him in the house and call the police — is a legitimate question. A question, in fact, that may well demand answers,” Bennett said in his written review of the in-custody death.

In his list of recommendations, Bennett again asked whether the state foster care response was adequate.

“When a foster parent contacts their foster agency to report that a foster child is in mental distress, does this state system owe a better response than a directive to call the police and not let the foster child re-enter the home?” he wrote.

DCF officials could not be reached for comment Monday. When a reporter called the DCF administrative officer’s ”foster care concerns” phone extension, a recorded message said the number is “currently not assigned to a staff member.”

The governor’s office has ordered an investigation into whether the agency’s policies and procedures were followed.

When Wichita police arrived at Lofton’s foster home, he was on the front porch. The teen was calm but appeared paranoid and was unable or unwilling to answer questions, WPD body camera footage shows.

Lofton asked police if they were there to protect him from people who wanted to hurt him. He also repeatedly asked what day it was.

Wichita police negotiated with Lofton for about an hour, trying to convince him to voluntarily go with them to Ascension Via Christi St. Joseph Hospital. At one point, an officer promised him they would take him to a hospital, not jail.

“Would you be willing to go to the hospital?” the officer asked while Lofton was on the porch of his foster home.

“Oh, wait. The hospital? Oh, (expletive). I thought y’all were talking about jail,” Lofton said.

“Just the hospital, man,” one officer said in the police body cam video. “I promise you, we’ll go to the hospital, not jail. We’re not going to take you to jail or nothin’.”

The teenager told officers he would rather sleep on his foster father’s porch than get checked out. When two officers pulled him to his feet, Lofton tried to break free.

When Lofton refused to go willingly, Wichita police grabbed him under his arms and began carrying him away from the porch. He broke loose of their grasp and sat down.

At that point, Wichita police officers began wrestling for physical control of Lofton and at least three officers held him down and cuffed his hands behind his back, video shows. Bennett’s report incorrectly states officers were “unable to get Cedric handcuffed.”

After Lofton was cuffed, he continued to resist and at one point kneed one of the officers in the forehead while he was being restrained against the side of the house, police body camera footage shows.

“Give me your (expletive) leg,” one of the officers said. He then kneed Lofton three times in the thigh while the other officers restrained Lofton’s arms and legs.

After that exchange, Lofton can be heard screaming, “They’re going to kill me.”

When Lofton resisted officers, they put him in ankle shackles and a WRAP restraint, a canvas wrapped around the legs, arms and lower torso while the person is in a seated position, then strapped to immobilize the person and keep them from harming themselves or others.

Outgoing Wichita Police Chief Gordon Ramsay and other department officials did not respond to written questions for this story.

Instead of taking Lofton to St. Joseph Hospital for a mental evaluation, police took him to the county-run Juvenile Intake and Assessment Center on four counts of battering an officer at 2:44 a.m.

The decision to transport him to JIAC was made by a Wichita police sergeant who Bennett’s report notes had not undergone crisis intervention training. At least one other officer said they would have still taken Lofton to the hospital, body cam footage shows.

“Whether officers should have taken Cedric to St. Joe instead of JIAC — given the information provided by the foster father that Cedric had been struggling mentally the last few days, and may have recently used K-2 (later toxicological analysis showed none present) — also presents a legitimate question,” Bennett said in his report.

“This is what your obligation is as an officer — to identify someone who’s in a mental health crisis and put them in the appropriate place,” said Hart, Lofton’s family attorney. “When is it up to the person in the mental health crisis to decide where they want to go or what they want to do or whether they want to comply?”

It’s unclear if Wichita police alerted corrections staff about Lofton’s mental state. Written reports by JIAC and juvenile detention officers do not mention a mental health crisis and instead note that Lofton was a “combative juvenile” who “appeared to be under the influence of some sort of drugs.”

County corrections employees noted in a special incident report obtained by The Eagle that, as a “corrective action” to prevent something like this from happening again, the facility should “require medical/mental health release prior to any youth being booked into JIAC who arrives in WRAP restraints.”

Sedgwick County revised their medical criteria for admission to JIAC to reflect this on Dec. 8. Wichita police used at least seven officers to restrain Lofton at his foster father’s house. But they left him under the supervision of a single JIAC intake specialist who didn’t have handcuffs or a stun gun.

“Whether this makes sense upon reflection, likewise raises a legitimate question,” Bennett wrote.

Five minutes after law enforcement left, the JIAC employee let Lofton out of the holding cell to begin the standard intake procedure.

Police were not called back to JIAC until 5:11 a.m., after corrections staff realized Lofton had no pulse.

The physical struggle that caused Lofton’s death began after Wichita police left JIAC, although the teen was still officially in police custody.

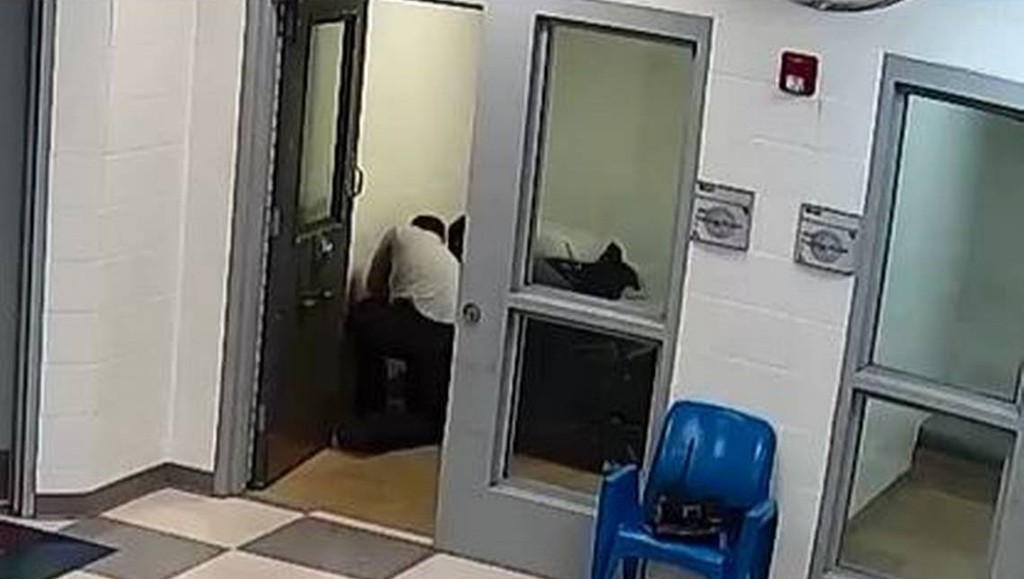

In video footage from the facility, which has no audio, Lofton appears calm but uncooperative. The situation appeared to escalate after the JIAC employee grabbed a jacket Lofton had placed on a chair in the lobby.

The JIAC employee can be seen pointing at the holding room. When Lofton did not go into the cell, the JIAC employee and another corrections worker grabbed him by the arms and tried to escort him to the cell.

As with his struggle with Wichita police, Lofton did not appear to become physically aggressive until after corrections staff initiated physical contact.

Lofton slipped the grip of one of the staff members and punched the JIAC employee in the face. He was then wrestled into the back of the holding cell and two other juvenile detention officers rushed into the cell.

Lofton was placed in leg shackles and then rolled face down onto the floor. Video shows the teen being physically restrained by multiple county staffers for at least 44 minutes and 43 seconds. He was rolled onto his back minutes after being handcuffed, and one detention officer began performing chest compressions.

“It does not appear that any of the four laid directly on top of or placed their weight on Cedric’s back/torso,” Bennett said in his report.

Police body camera footage shows at least one of the employees acknowledged applying force to Lofton’s back in the immediate aftermath of the struggle.

“Yeah, just onto his back,” a corrections officer told Wichita police when asked whether he applied weight to Lofton’s back. “Like his shoulders and back area. All I had was just my elbow or like my forearm, and that was it.”

He went on to say that another employee who was restraining Lofton’s other arm applied a similar amount of force to his back.

“Had anyone put their full weight on his back/chest for an extended period of time during this struggle, it is hard to imagine Cedric could have remained conscious and struggling for 35 minutes,” Bennett said in his report.

It is unclear how long Lofton continued to struggle or remained conscious while face down in the concrete cell.

In a video released by the county, Lofton is rarely visible under the huddled JIAC and JDF workers as they restrain him on the floor.

Bennett said he can’t say definitively when Lofton lost consciousness.

“I wrestled with that because [corrections staff] were not entirely consistent whether it was a second before or three seconds after [Lofton was cuffed] or whatever,” Bennett said. “And frankly, I’m not sure that they in the moment were — ‘When did you become aware? ‘ may be a better question. When did you become aware that he had relaxed or gone limp?’”

In a use of force report obtained through the Kansas Open Records Act, one officer said they held Lofton down until he appeared to be “snoring.”

”Once we believed the resident had exhausted himself to sleep I released my hold,” the employee wrote. Another county employee suggested they feared for their lives. “We were able to place him in cuffs but he continued to struggle and threaten to kill staff if we let him up.”

“They were trying to push his arms back and trying to get him handcuffed, and none of them were skilled enough or trained enough or whatever, or able for whatever reason to get him cuffed,” Bennett said in an interview with The Eagle.

“There are contradictions, you know, anytime someone describes what they did, but I’m trying to get to the big picture here and go, ‘OK. what were they doing?’” Bennett said. “If he’d have said, ‘I let go of his arm and I just pushed with all my might against the middle of his back and held him down, I’d have included that in there.”

The civil rights lawyer questioned the weight Bennett placed on the county corrections officers’ accounts.

“You’re going to believe on face value what they say?” Hart said. “Since when has a district attorney said, ‘An accused said he didn’t do it so he didn’t do it?”

At a news conference after Bennett announced he was declining charges, Sedgwick County Corrections Director Glenda Martens said “employees acted well within the policy and the requirements of that policy” when they restrained the teen.

Per JIAC’s use of force policy, “Mechanical restraints (shackles, handcuffs) shall be used only when necessary as a control to prevent a resident from harming themselves or others while being moved to a secured room.”

The policy states that restraints should not be used for more than 30 minutes without the approval of corrections supervisors. Two of the juvenile staff who restrained Lofton were supervisors.

Bennett said the county employees were immune from prosecution because they were protecting themselves during the ongoing struggle with the teen.

Hart said no reasonable person would believe Lofton posed a threat to the adults in the room as he lay shackled face down in the holding room.

“They didn’t fear for their safety. It’s very obvious through the view of the video, they didn’t fear for their safety,” Hart said.

“He was subdued,” he said. “That’s what we call being subdued. And you know what Bennett said to that? He continued to struggle. That’s why they had a right to kill him. Even though he was shackled, he struggled.”

Bennett told The Eagle he was unsure why corrections staff didn’t leave Lofton to calm down alone in the holding room.

“The answer to the question that they gave . . . is that they can’t, per policy, leave him unattended, shackled, which doesn’t answer your question, which is, unshackle him for Christ’s sake,” Bennett said.

“But again, you don’t judge them on what they didn’t do. You judge them on what they did, as dissatisfying of an answer as that may be.”

Bennett said the investigation produced no evidence that corrections staff killed Lofton intentionally, knowingly or recklessly, as defined by state law.

“The notion that they acted ‘recklessly’ — for instance, to establish involuntary manslaughter for recklessly causing Cedric’s death — might sound appropriate in the general sense of the word, but this conclusion is not supported by the specific definition of ‘reckless’ in Kansas law,” his report states.

Kansas has no negligent homicide law on the books.