Wichita at center of abortion debate

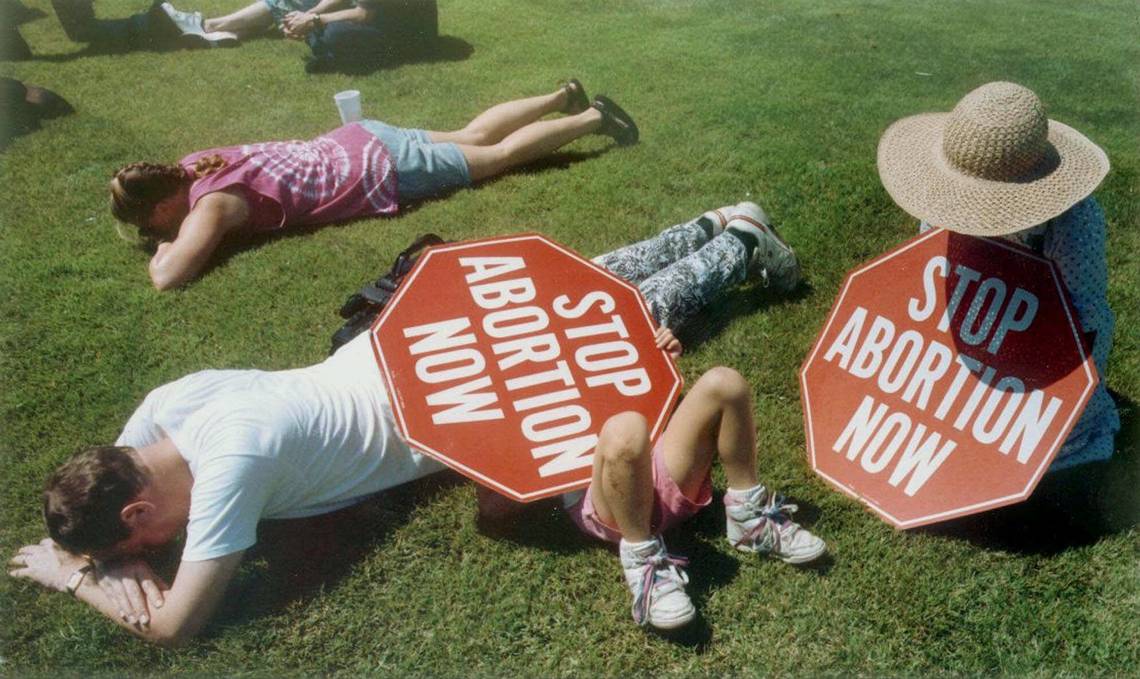

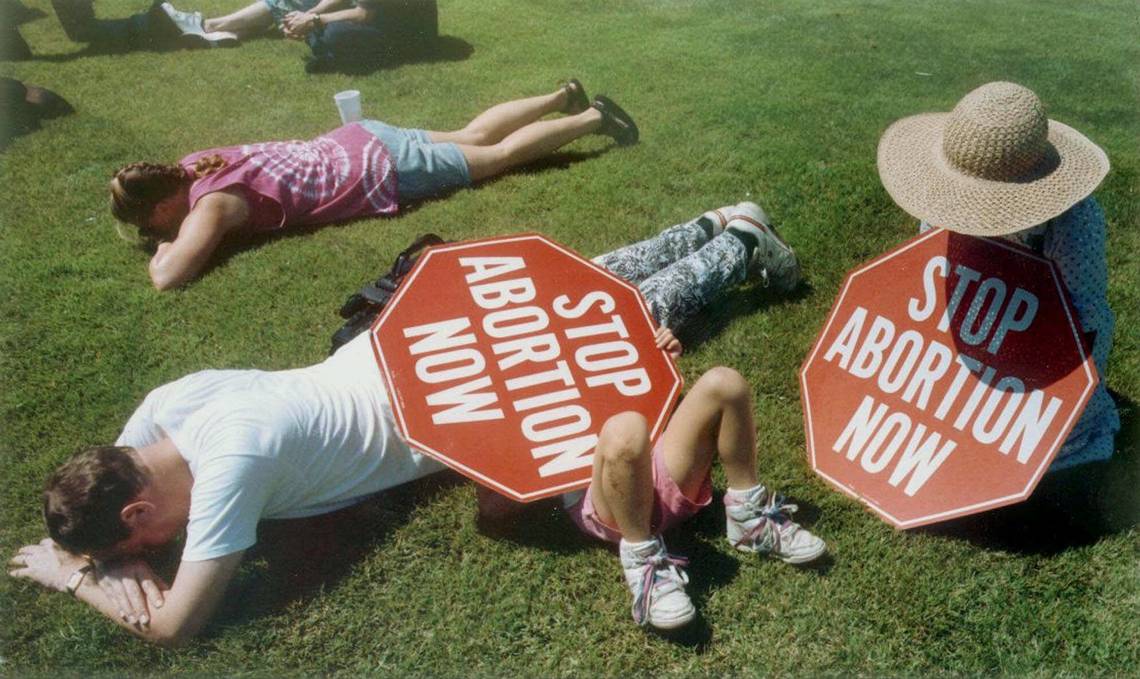

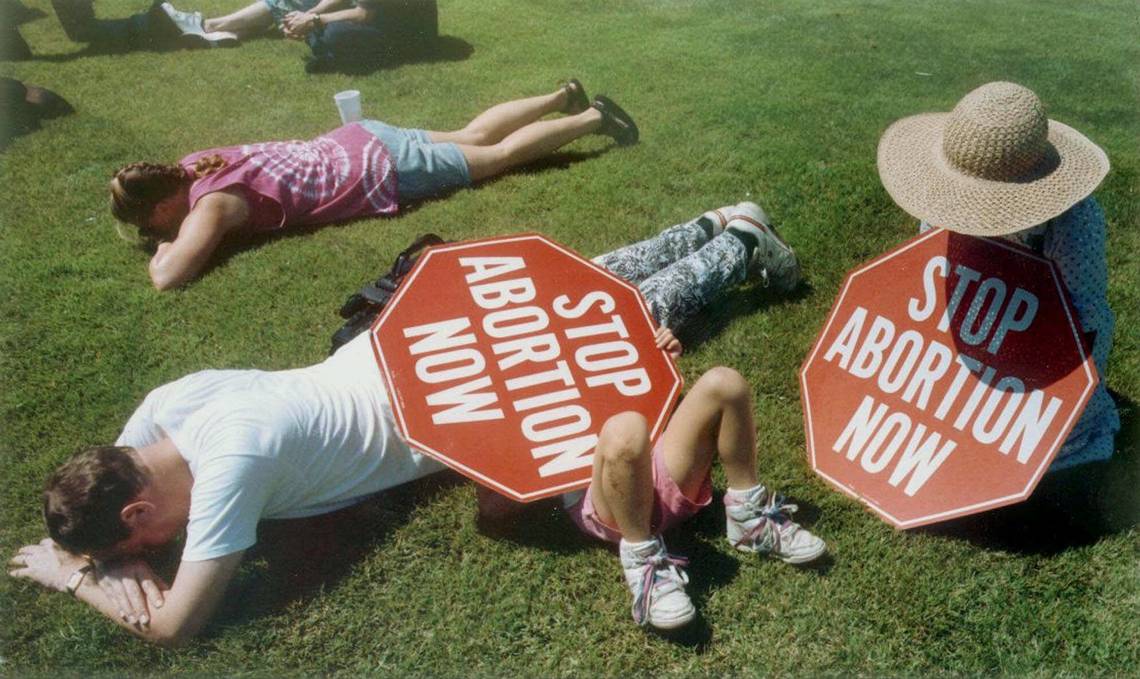

Abortion protesters pray on the lawn of Wichita City Hall during the 1991 Summer of Mercy. They were there in support of jailed protesters. File THE WICHITA EAGLE

Abortion protesters pray on the lawn of Wichita City Hall during the 1991 Summer of Mercy. They were there in support of jailed protesters. File THE WICHITA EAGLE

People who were there recall Summer of Mercy

People who were there recall Summer of Mercy

People who were there recall Summer of Mercy

by matthew Kelly

July 28, 2022

by matthew Kelly

July 28, 2022

by matthew Kelly

July 28, 2022

In the sweltering heat of summer, defiant protesters blocked cars with their bodies and barricaded the entrances to Wichita abortion clinics.

It was 1991, deemed the Summer of Mercy by protest organizers. Tens of thousands of people staged disruptive demonstrations that lasted for six weeks and placed Wichita at the epicenter of a divisive national debate on reproductive health.

“Many of us felt like that, for a time at least, Wichita was the Selma, Alabama, of the abortion-rights movement or the pro-life movement,” said John Carmichael, who volunteered to escort patients at abortion clinics during the demonstrations.

Three decades later, Kansas is again at the forefront of the national struggle over abortion. On Aug. 2, residents will become the first to hold a statewide vote on abortion rights since the U.S. Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade’s federal right to an abortion in June.

As people go to the polls, some are remembering that time not so long ago when the national spotlight found Wichita grappling with a social disobedience campaign that redefined the fight over abortion access in America.

Abortion opponents pray in front of George Tiller’s clinic in August 1991. Mike Hutmacher Wichita Eagle

Abortion opponents pray in front of George Tiller’s clinic in August 1991. Mike Hutmacher Wichita Eagle

SUMMER OF MERCY

SUMMER OF MERCY

SUMMER OF MERCY

The standoff between abortion opponents and abortion rights supporters in the Kansas heartland captured the country’s imagination in July and August 1991, when an army of activists descended on Wichita.

The protests were an intentionally disruptive call to action for social conservatives, said Keith Tucci, the former director of Operation Rescue National, who was rebuked by some for branding abortion “the American Holocaust.”

“Looking back, I think there were a lot of people that were ready to do something, and many of them didn’t even know they were ready to do something,” Tucci told The Eagle in a phone interview. “But when they saw the opportunity to make a difference, they decided it was worth the risk to do that and worth the unpopularity to do it.”

Over 42 days, Wichita police arrested protesters some 2,600 times for attempting to prevent women from entering abortion facilities, including the clinic of Dr. George Tiller, who was known for performing late-term abortions and who 18 years later was assassinated by an anti-abortion extremist.

The 1991 campaign was branded the Summer of Mercy by organizers. But that’s not how everyone remembers it.

“We referred to it as the Summer of Hell,” said Meghan Bean, an abortion-rights activist whose mother ran the Comfort Inn hotel that hosted Tiller’s out-of-town patients. Bean was 13 years old when Operation Rescue came to Wichita.

“That summer, I remember the violence and the hate,” she said.

Among the people who felt called to action was Troy Newman, now the president of Operation Rescue, who had his first experience protesting abortion in Wichita.

“I was young. I was in Bible college and someone showed me a picture of an aborted baby — a late-term aborted baby . . . and I said to myself, that’s not happening in this country. How can people kill a baby in the seventh, eighth month?” Newman said. “And they said yeah, they’re doing it and not only that. They’re doing it in the Midwest in Wichita, Kansas, and we’re all going out there. So that was it.”

The standoff between abortion opponents and abortion rights supporters in the Kansas heartland captured the country’s imagination in July and August 1991, when an army of activists descended on Wichita.

The protests were an intentionally disruptive call to action for social conservatives, said Keith Tucci, the former director of Operation Rescue National, who was rebuked by some for branding abortion “the American Holocaust.”

“Looking back, I think there were a lot of people that were ready to do something, and many of them didn’t even know they were ready to do something,” Tucci told The Eagle in a phone interview. “But when they saw the opportunity to make a difference, they decided it was worth the risk to do that and worth the unpopularity to do it.”

Over 42 days, Wichita police arrested protesters some 2,600 times for attempting to prevent women from entering abortion facilities, including the clinic of Dr. George Tiller, who was known for performing late-term abortions and who 18 years later was assassinated by an anti-abortion extremist.

The 1991 campaign was branded the Summer of Mercy by organizers. But that’s not how everyone remembers it.

“We referred to it as the Summer of Hell,” said Meghan Bean, an abortion-rights activist whose mother ran the Comfort Inn hotel that hosted Tiller’s out-of-town patients. Bean was 13 years old when Operation Rescue came to Wichita.

“That summer, I remember the violence and the hate,” she said.

Among the people who felt called to action was Troy Newman, now the president of Operation Rescue, who had his first experience protesting abortion in Wichita.

“I was young. I was in Bible college and someone showed me a picture of an aborted baby — a late-term aborted baby . . . and I said to myself, that’s not happening in this country. How can people kill a baby in the seventh, eighth month?” Newman said. “And they said yeah, they’re doing it and not only that. They’re doing it in the Midwest in Wichita, Kansas, and we’re all going out there. So that was it.”

The standoff between abortion opponents and abortion rights supporters in the Kansas heartland captured the country’s imagination in July and August 1991, when an army of activists descended on Wichita.

The protests were an intentionally disruptive call to action for social conservatives, said Keith Tucci, the former director of Operation Rescue National, who was rebuked by some for branding abortion “the American Holocaust.”

“Looking back, I think there were a lot of people that were ready to do something, and many of them didn’t even know they were ready to do something,” Tucci told The Eagle in a phone interview. “But when they saw the opportunity to make a difference, they decided it was worth the risk to do that and worth the unpopularity to do it.”

Over 42 days, Wichita police arrested protesters some 2,600 times for attempting to prevent women from entering abortion facilities, including the clinic of Dr. George Tiller, who was known for performing late-term abortions and who 18 years later was assassinated by an anti-abortion extremist.

The 1991 campaign was branded the Summer of Mercy by organizers. But that’s not how everyone remembers it.

“We referred to it as the Summer of Hell,” said Meghan Bean, an abortion-rights activist whose mother ran the Comfort Inn hotel that hosted Tiller’s out-of-town patients. Bean was 13 years old when Operation Rescue came to Wichita.

“That summer, I remember the violence and the hate,” she said.

Among the people who felt called to action was Troy Newman, now the president of Operation Rescue, who had his first experience protesting abortion in Wichita.

“I was young. I was in Bible college and someone showed me a picture of an aborted baby — a late-term aborted baby . . . and I said to myself, that’s not happening in this country. How can people kill a baby in the seventh, eighth month?” Newman said. “And they said yeah, they’re doing it and not only that. They’re doing it in the Midwest in Wichita, Kansas, and we’re all going out there. So that was it.”

WHY WICHITA?

WHY WICHITA?

WHY WICHITA?

In the two decades before the Summer of Mercy, Kansas was known as an abortion-rights stronghold. Republican majorities amended the state’s criminal statute in 1969 to allow for abortions in cases of rape, incest, threats to maternal health and fetal deformity.

By 1974, the rate of legal abortions in Kansas was three times the rate in Nebraska, seven times the rate in Missouri and 25 times the rate in Oklahoma, according to National Abortion Rights Action League records.

But a Christian conservative coalition was strengthening. In a show of political force, they transcended party lines to help elect Democrat Joan Finney governor over moderate Republican incumbent Mike Hayden in 1990 after she came out against abortion.

Wichita anti-abortion activists first contacted Tucci about protesting outside Tiller’s clinic in December 1990, a month after Finney’s election.

Operation Rescue, a collection of anti-abortion activist groups, was honing in on a location for its next major demonstration in the summer of ’91 when Tucci said he received a divine directive.

“The real story is this — God spoke to my heart,” Tucci said.

“Bloody Kansas earned its name from the pro-life people who wanted to stop slavery, and I felt like God really put it in my heart that he was going to honor the sacrifice that they made. That there was ‘seed in the ground,’ was the exact phrase that I heard in my heart.”

When protesters arrived in Wichita on July 15, the police department had negotiated with administrators at all three of the city’s abortion providers to close clinics during the scheduled week of protests to avoid conflict.

“The word was that these people were going to be here for a week and they were going to leave, and that Dr. Tiller didn’t want pro-choice people out in front of his clinic because he felt like it would just make things worse,” said Carmichael, who is now a Democratic state legislator.

As Jennifer Donnally notes in her 2016 essay, “The Untold History Behind the 1991 Summer of Mercy,” published in the Kansas History journal, negotiating the closure of abortion clinics during the initial week of protests proved to be a pivotal decision.

“National anti-abortion phone hotlines spread the good news throughout the country. For the first time in its existence, Operation Rescue had managed to shut down an entire city’s abortion providers,” Donnally wrote. “The hotlines spoke of God’s providence at work, attracting more protesters from across the nation.”

That’s when Operation Rescue announced that it would stay in the city indefinitely.

“People came for a weekend and ended up staying four or five weeks,” Tucci recalls.

“The significance of the Summer of Mercy is, it brought people out of the stands and onto the playing field. Many, many pro-life spectators who understood that being on the street was very significant to how this thing was going to turn.”

In the two decades before the Summer of Mercy, Kansas was known as an abortion-rights stronghold. Republican majorities amended the state’s criminal statute in 1969 to allow for abortions in cases of rape, incest, threats to maternal health and fetal deformity.

By 1974, the rate of legal abortions in Kansas was three times the rate in Nebraska, seven times the rate in Missouri and 25 times the rate in Oklahoma, according to National Abortion Rights Action League records.

But a Christian conservative coalition was strengthening. In a show of political force, they transcended party lines to help elect Democrat Joan Finney governor over moderate Republican incumbent Mike Hayden in 1990 after she came out against abortion.

Wichita anti-abortion activists first contacted Tucci about protesting outside Tiller’s clinic in December 1990, a month after Finney’s election.

Operation Rescue, a collection of anti-abortion activist groups, was honing in on a location for its next major demonstration in the summer of ’91 when Tucci said he received a divine directive.

“The real story is this — God spoke to my heart,” Tucci said.

“Bloody Kansas earned its name from the pro-life people who wanted to stop slavery, and I felt like God really put it in my heart that he was going to honor the sacrifice that they made. That there was ‘seed in the ground,’ was the exact phrase that I heard in my heart.”

When protesters arrived in Wichita on July 15, the police department had negotiated with administrators at all three of the city’s abortion providers to close clinics during the scheduled week of protests to avoid conflict.

“The word was that these people were going to be here for a week and they were going to leave, and that Dr. Tiller didn’t want pro-choice people out in front of his clinic because he felt like it would just make things worse,” said Carmichael, who is now a Democratic state legislator.

As Jennifer Donnally notes in her 2016 essay, “The Untold History Behind the 1991 Summer of Mercy,” published in the Kansas History journal, negotiating the closure of abortion clinics during the initial week of protests proved to be a pivotal decision.

“National anti-abortion phone hotlines spread the good news throughout the country. For the first time in its existence, Operation Rescue had managed to shut down an entire city’s abortion providers,” Donnally wrote. “The hotlines spoke of God’s providence at work, attracting more protesters from across the nation.”

That’s when Operation Rescue announced that it would stay in the city indefinitely.

“People came for a weekend and ended up staying four or five weeks,” Tucci recalls.

“The significance of the Summer of Mercy is, it brought people out of the stands and onto the playing field. Many, many pro-life spectators who understood that being on the street was very significant to how this thing was going to turn.”

Wichita police officers attempt to remove an abortion protester from under a car at the entrance to George Tiller’s clinic during the Summer of Mercy protest in 1991. Jeff Tuttle The Wichita Eagle

Wichita police officers attempt to remove an abortion protester from under a car at the entrance to George Tiller’s clinic during the Summer of Mercy protest in 1991. Jeff Tuttle The Wichita Eagle

CHAOS IN WICHITA

CHAOS IN WICHITA

After a week, clinics reopened. The Wichita Police Department arrested 14 people on July 22, the eighth day of protests, when demonstrators blocked a woman from entering the Wichita Family Planning clinic on East Central. Tucci was one of the first to be arrested.

The rate of arrests climbed exponentially after that, totaling 1,175 by July 29 as local and out-of-state protesters alike laid down in the street and threw themselves in front of cars, forming human chains in an attempt to keep patients and staff from gaining access to abortion facilities.

“We took an absolute page from the playbook of Dr. Martin Luther King in the civil rights movement,” Newman said. “They didn’t fight back.”

Operation Rescue required demonstrators to sign a pledge of nonviolence. “We were peaceful, nonviolent,” Newman said.

“We were on our knees or sitting. And if they beat us up, so be it. They drug us off to jail. We came back and did it again.”

The Eagle reported that some protesters were arrested as many as seven times. They were rarely held for long and refused to pay fines.

“It was like catch and release, you know? By the time we filled out the paperwork, they were already released and back out to the clinic,” former Wichita Police Chief Rick Stone told The Eagle in a phone interview this summer.

Mayor Bob Knight, a Republican and abortion opponent, was slow to discourage protesters’ tactics, instead aiming his ire at what he saw as an excessive police response. Knight took exception to Stone’s decision to deploy mounted officers to control crowds on July 22 and sided with protesters who complained when arresting officers loaded them into rental trucks with inadequate ventilation.

In an interview with The Eagle, Knight, now 81, said the city “made some mistakes” in its handling of the protests.

“I think we had a police chief who overreacted,” he said.

“He really kind of had a General Patton complex, you know? He wanted helicopters.”

After the protests, Stone was honored with the Law Enforcement Officer of the Year Award from the U.S. Marshals Service, alongside Sedgwick County Sheriff Mike Hill.

But the personality clash between city officials amplified the chaos of the summer. Knight and City Manager Chris Cherches issued a directive instructing police to apprehend protesters obstructing clinic access using the “least-confrontational means” possible. Arrests were only to be made after demonstrators blocked clinic gates.

“That just poured fuel on the fire,” Stone said of the City Hall directive. “As soon as the protesters received this . . . they got on the phone and they were calling Oregon and Michigan and New York, California, Texas, and pretty soon, we had hundreds of people showing up because they knew we were instructed to enforce the law in the least-confrontational manner.”

Operation Rescue activists developed a tactic they called the “baby walk” that involved taking tiny steps toward the police transport vehicle.

“Sitting in front of the doors to an abortion clinic, it takes a long time to haul off 100 people, and if we go limp — in other words, we don’t walk when we’re arrested — they would have to carry us,” Newman said. “That was a problem for the police officers. They had to carry 100 people in 100-degree weather and it was hurting their backs and hurting the pro-lifers so we came to a negotiation that we would walk.”

As long as protesters were moving toward police vehicles, officers were instructed not to intervene.

In a July 27, 1991 Eagle article, Peggy Jarman, a spokesperson for Tiller, complained that police were being too lenient with protesters.

“As long as the decision remains that these people will be placated, we are in anarchy,” Jarman said. “I watched them take four hours to arrest 107 people. I watched them take their baby steps. I watched while our patients were harassed without mercy, with no compassion, in the most brutal of ways.”

After a week, clinics reopened. The Wichita Police Department arrested 14 people on July 22, the eighth day of protests, when demonstrators blocked a woman from entering the Wichita Family Planning clinic on East Central. Tucci was one of the first to be arrested.

The rate of arrests climbed exponentially after that, totaling 1,175 by July 29 as local and out-of-state protesters alike laid down in the street and threw themselves in front of cars, forming human chains in an attempt to keep patients and staff from gaining access to abortion facilities.

“We took an absolute page from the playbook of Dr. Martin Luther King in the civil rights movement,” Newman said. “They didn’t fight back.”

Operation Rescue required demonstrators to sign a pledge of nonviolence. “We were peaceful, nonviolent,” Newman said.

“We were on our knees or sitting. And if they beat us up, so be it. They drug us off to jail. We came back and did it again.”

The Eagle reported that some protesters were arrested as many as seven times. They were rarely held for long and refused to pay fines.

“It was like catch and release, you know? By the time we filled out the paperwork, they were already released and back out to the clinic,” former Wichita Police Chief Rick Stone told The Eagle in a phone interview this summer.

Mayor Bob Knight, a Republican and abortion opponent, was slow to discourage protesters’ tactics, instead aiming his ire at what he saw as an excessive police response. Knight took exception to Stone’s decision to deploy mounted officers to control crowds on July 22 and sided with protesters who complained when arresting officers loaded them into rental trucks with inadequate ventilation.

In an interview with The Eagle, Knight, now 81, said the city “made some mistakes” in its handling of the protests.

“I think we had a police chief who overreacted,” he said.

“He really kind of had a General Patton complex, you know? He wanted helicopters.”

After the protests, Stone was honored with the Law Enforcement Officer of the Year Award from the U.S. Marshals Service, alongside Sedgwick County Sheriff Mike Hill.

But the personality clash between city officials amplified the chaos of the summer. Knight and City Manager Chris Cherches issued a directive instructing police to apprehend protesters obstructing clinic access using the “least-confrontational means” possible. Arrests were only to be made after demonstrators blocked clinic gates.

“That just poured fuel on the fire,” Stone said of the City Hall directive. “As soon as the protesters received this . . . they got on the phone and they were calling Oregon and Michigan and New York, California, Texas, and pretty soon, we had hundreds of people showing up because they knew we were instructed to enforce the law in the least-confrontational manner.”

Operation Rescue activists developed a tactic they called the “baby walk” that involved taking tiny steps toward the police transport vehicle.

“Sitting in front of the doors to an abortion clinic, it takes a long time to haul off 100 people, and if we go limp — in other words, we don’t walk when we’re arrested — they would have to carry us,” Newman said. “That was a problem for the police officers. They had to carry 100 people in 100-degree weather and it was hurting their backs and hurting the pro-lifers so we came to a negotiation that we would walk.”

As long as protesters were moving toward police vehicles, officers were instructed not to intervene.

In a July 27, 1991 Eagle article, Peggy Jarman, a spokesperson for Tiller, complained that police were being too lenient with protesters.

“As long as the decision remains that these people will be placated, we are in anarchy,” Jarman said. “I watched them take four hours to arrest 107 people. I watched them take their baby steps. I watched while our patients were harassed without mercy, with no compassion, in the most brutal of ways.”

WEIGHING RIGHTS

Two weeks into the protest, the WPD had spent 55% of the department’s budgeted overtime pay for the year responding to the demonstrations. On July 30, Cherches estimated that demonstrations had already cost the city $400,000.

More than two-thirds of readers polled by The Eagle at the time, including many who opposed abortion, said they disagreed with Operation Rescue’s confrontational antics outside the clinics.

In her Wichita speech to Operation Rescue supporters on Aug. 2, the governor voiced her support for their cause. Finney asked protesters to work within the law but did not directly discourage them from blocking clinic entrances, going as far as to praise their tactics.

“I commend you for the orderly manner in which you have conducted the demonstration,” Finney said.

“Civil disobedience is one thing. I say biblical obedience,” Tucci, the Operation Rescue leader, told The Eagle this summer. “Because I’m not trying to be disobedient to anybody. I’m trying to be obedient to God. When God’s laws and man’s laws conflict, I think as a Christian, as a follower of Christ, I have to choose God’s laws.”

That logic didn’t go over well with U.S. District Court Judge Patrick Kelly, who issued an injunction ordering demonstrators to stop blocking access to clinic entrances and later called in the U.S. Marshals to enforce the order under an 1871 federal law prohibiting conspiracies designed to deprive citizens of their civil rights.

Operation Rescue founder Randall Terry lashed out at Kelly in response, deriding him as a “Nazi judge” and an “egotistical tyrant.”

“Judge Kelly has made himself the governor, the mayor, the chief of police, the jailor and the prosecutor,” Terry said. “He has issued a challenge to the Church. And he has shown incredible bigotry against Christians.”

Kelly died in 2007. Carmichael said he knew him well from when the judge served as scoutmaster of his Boy Scout troop.

“Judge Kelly was a devout Roman Catholic,” Carmichael said. “He was born and raised in the Catholic Church. I never knew what his own personal belief about abortion was but his commitment was to the law, and the law was pretty darn clear, so he proceeded to enforce that law.”

Operation Rescue demonstrators weren’t the only ones who claimed Kelly overstepped his authority in his efforts to bring protesters to heel.

Working on behalf of the George H.W. Bush administration, future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts filed a motion arguing that the 1871 law, enacted to protect Black people from Ku Klux Klan violence, did not apply to patients seeking abortions. Thus, he reasoned, it was improper for Kelly to call in the marshals.

Although an appeals court struck down Kelly’s decision, Congress eventually affirmed his intent with the passage of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1994, which made it a federal crime to physically obstruct access to a clinic entrance or intimidate abortion patients and clinic staff.

WEIGHING RIGHTS

WEIGHING RIGHTS

CHAOS IN WICHITA

Two weeks into the protest, the WPD had spent 55% of the department’s budgeted overtime pay for the year responding to the demonstrations. On July 30, Cherches estimated that demonstrations had already cost the city $400,000.

More than two-thirds of readers polled by The Eagle at the time, including many who opposed abortion, said they disagreed with Operation Rescue’s confrontational antics outside the clinics.

In her Wichita speech to Operation Rescue supporters on Aug. 2, the governor voiced her support for their cause. Finney asked protesters to work within the law but did not directly discourage them from blocking clinic entrances, going as far as to praise their tactics.

“I commend you for the orderly manner in which you have conducted the demonstration,” Finney said.

“Civil disobedience is one thing. I say biblical obedience,” Tucci, the Operation Rescue leader, told The Eagle this summer. “Because I’m not trying to be disobedient to anybody. I’m trying to be obedient to God. When God’s laws and man’s laws conflict, I think as a Christian, as a follower of Christ, I have to choose God’s laws.”

That logic didn’t go over well with U.S. District Court Judge Patrick Kelly, who issued an injunction ordering demonstrators to stop blocking access to clinic entrances and later called in the U.S. Marshals to enforce the order under an 1871 federal law prohibiting conspiracies designed to deprive citizens of their civil rights.

Operation Rescue founder Randall Terry lashed out at Kelly in response, deriding him as a “Nazi judge” and an “egotistical tyrant.”

“Judge Kelly has made himself the governor, the mayor, the chief of police, the jailor and the prosecutor,” Terry said. “He has issued a challenge to the Church. And he has shown incredible bigotry against Christians.”

Kelly died in 2007. Carmichael said he knew him well from when the judge served as scoutmaster of his Boy Scout troop.

“Judge Kelly was a devout Roman Catholic,” Carmichael said. “He was born and raised in the Catholic Church. I never knew what his own personal belief about abortion was but his commitment was to the law, and the law was pretty darn clear, so he proceeded to enforce that law.”

Operation Rescue demonstrators weren’t the only ones who claimed Kelly overstepped his authority in his efforts to bring protesters to heel.

Working on behalf of the George H.W. Bush administration, future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts filed a motion arguing that the 1871 law, enacted to protect Black people from Ku Klux Klan violence, did not apply to patients seeking abortions. Thus, he reasoned, it was improper for Kelly to call in the marshals.

Although an appeals court struck down Kelly’s decision, Congress eventually affirmed his intent with the passage of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1994, which made it a federal crime to physically obstruct access to a clinic entrance or intimidate abortion patients and clinic staff.

Two weeks into the protest, the WPD had spent 55% of the department’s budgeted overtime pay for the year responding to the demonstrations. On July 30, Cherches estimated that demonstrations had already cost the city $400,000.

More than two-thirds of readers polled by The Eagle at the time, including many who opposed abortion, said they disagreed with Operation Rescue’s confrontational antics outside the clinics.

In her Wichita speech to Operation Rescue supporters on Aug. 2, the governor voiced her support for their cause. Finney asked protesters to work within the law but did not directly discourage them from blocking clinic entrances, going as far as to praise their tactics.

“I commend you for the orderly manner in which you have conducted the demonstration,” Finney said.

“Civil disobedience is one thing. I say biblical obedience,” Tucci, the Operation Rescue leader, told The Eagle this summer. “Because I’m not trying to be disobedient to anybody. I’m trying to be obedient to God. When God’s laws and man’s laws conflict, I think as a Christian, as a follower of Christ, I have to choose God’s laws.”

That logic didn’t go over well with U.S. District Court Judge Patrick Kelly, who issued an injunction ordering demonstrators to stop blocking access to clinic entrances and later called in the U.S. Marshals to enforce the order under an 1871 federal law prohibiting conspiracies designed to deprive citizens of their civil rights.

Operation Rescue founder Randall Terry lashed out at Kelly in response, deriding him as a “Nazi judge” and an “egotistical tyrant.”

“Judge Kelly has made himself the governor, the mayor, the chief of police, the jailor and the prosecutor,” Terry said. “He has issued a challenge to the Church. And he has shown incredible bigotry against Christians.”

Kelly died in 2007. Carmichael said he knew him well from when the judge served as scoutmaster of his Boy Scout troop.

“Judge Kelly was a devout Roman Catholic,” Carmichael said. “He was born and raised in the Catholic Church. I never knew what his own personal belief about abortion was but his commitment was to the law, and the law was pretty darn clear, so he proceeded to enforce that law.”

Operation Rescue demonstrators weren’t the only ones who claimed Kelly overstepped his authority in his efforts to bring protesters to heel.

Working on behalf of the George H.W. Bush administration, future Supreme Court Chief Justice John Roberts filed a motion arguing that the 1871 law, enacted to protect Black people from Ku Klux Klan violence, did not apply to patients seeking abortions. Thus, he reasoned, it was improper for Kelly to call in the marshals.

Although an appeals court struck down Kelly’s decision, Congress eventually affirmed his intent with the passage of the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1994, which made it a federal crime to physically obstruct access to a clinic entrance or intimidate abortion patients and clinic staff.

After a week, clinics reopened. The Wichita Police Department arrested 14 people on July 22, the eighth day of protests, when demonstrators blocked a woman from entering the Wichita Family Planning clinic on East Central. Tucci was one of the first to be arrested.

The rate of arrests climbed exponentially after that, totaling 1,175 by July 29 as local and out-of-state protesters alike laid down in the street and threw themselves in front of cars, forming human chains in an attempt to keep patients and staff from gaining access to abortion facilities.

“We took an absolute page from the playbook of Dr. Martin Luther King in the civil rights movement,” Newman said. “They didn’t fight back.”

Operation Rescue required demonstrators to sign a pledge of nonviolence. “We were peaceful, nonviolent,” Newman said.

“We were on our knees or sitting. And if they beat us up, so be it. They drug us off to jail. We came back and did it again.”

The Eagle reported that some protesters were arrested as many as seven times. They were rarely held for long and refused to pay fines.

“It was like catch and release, you know? By the time we filled out the paperwork, they were already released and back out to the clinic,” former Wichita Police Chief Rick Stone told The Eagle in a phone interview this summer.

Mayor Bob Knight, a Republican and abortion opponent, was slow to discourage protesters’ tactics, instead aiming his ire at what he saw as an excessive police response. Knight took exception to Stone’s decision to deploy mounted officers to control crowds on July 22 and sided with protesters who complained when arresting officers loaded them into rental trucks with inadequate ventilation.

In an interview with The Eagle, Knight, now 81, said the city “made some mistakes” in its handling of the protests.

“I think we had a police chief who overreacted,” he said.

“He really kind of had a General Patton complex, you know? He wanted helicopters.”

After the protests, Stone was honored with the Law Enforcement Officer of the Year Award from the U.S. Marshals Service, alongside Sedgwick County Sheriff Mike Hill.

But the personality clash between city officials amplified the chaos of the summer. Knight and City Manager Chris Cherches issued a directive instructing police to apprehend protesters obstructing clinic access using the “least-confrontational means” possible. Arrests were only to be made after demonstrators blocked clinic gates.

“That just poured fuel on the fire,” Stone said of the City Hall directive. “As soon as the protesters received this . . . they got on the phone and they were calling Oregon and Michigan and New York, California, Texas, and pretty soon, we had hundreds of people showing up because they knew we were instructed to enforce the law in the least-confrontational manner.”

Operation Rescue activists developed a tactic they called the “baby walk” that involved taking tiny steps toward the police transport vehicle.

“Sitting in front of the doors to an abortion clinic, it takes a long time to haul off 100 people, and if we go limp — in other words, we don’t walk when we’re arrested — they would have to carry us,” Newman said. “That was a problem for the police officers. They had to carry 100 people in 100-degree weather and it was hurting their backs and hurting the pro-lifers so we came to a negotiation that we would walk.”

As long as protesters were moving toward police vehicles, officers were instructed not to intervene.

In a July 27, 1991 Eagle article, Peggy Jarman, a spokesperson for Tiller, complained that police were being too lenient with protesters.

“As long as the decision remains that these people will be placated, we are in anarchy,” Jarman said. “I watched them take four hours to arrest 107 people. I watched them take their baby steps. I watched while our patients were harassed without mercy, with no compassion, in the most brutal of ways.”

A group of abortion rights advocates cheer and clap during the Speak Out for Choice rally at A. Price Woodard Park during the summer of 1991. Laura Rauch The Wichita Eagle

A group of abortion rights advocates cheer and clap during the Speak Out for Choice rally at A. Price Woodard Park during the summer of 1991. Laura Rauch The Wichita Eagle

ABORTION-RIGHTS RESPONSE

ABORTION-RIGHTS RESPONSE

ABORTION-RIGHTS RESPONSE

As the summer wore on, protesters’ confrontational actions increasingly aggravated abortion-rights supporters.

Some, like Carmichael, resented that police had instructed counter-protesters not to demonstrate on clinic property, even as Operation Rescue attempted to block entrances.

“There were some of us who were really appalled that pro-life people were on the private property and pro-choice people were being kept off the property,” Carmichael said. “So there were three or four of us who got together and decided we needed to probably start trying to organize pro-choice people to take an approach which Dr. Tiller’s practice did not at least initially encourage, and that was to call out pro-choice people with signs and tell the police department that we were no longer going to stand across the street.”

Abortion-rights forces were stationed at a house two doors south of Tiller’s clinic at the Pro-Choice Action League headquarters. That’s where Bean, whose mother ran the hotel that accommodated Tiller’s patients, spent much of her summer.

“Back in ’91, it was my grandmother, my mother, [my sister] and myself,” Bean said.

“That’s when my family got started in the whole abortion political — it’s a warfare is what it is really.”

Even at a young age, she understood she was in the middle of something important.

“My mom explained it to us very simple,” Bean said. “She just explained to us that there was a group of people who were saying that women could not choose what they wanted to do with their bodies.”

Most of the time, she had to stay inside the house.

“There was so much violence that went on,” Bean said. “Bomb threats were being made. At one point of time, my sister was in the clinic and there was a threat that was made that there was a bomb inside the clinic, and so the bomb squad had to come out.”

Carmichael and others volunteered to help escort patients in and out of clinics, shielding them from as much intimidation and vitriol as possible. Sometimes, it was Carmichael’s job to distract protesters while a patient was being snuck in through an alternate clinic entrance.

Sometimes they used decoy patients to gauge the opposition’s tactics for the day.

Other times, police had to take over patient escort duties.

“Patients had to park down the street and around the corner (from Tiller’s clinic),” Bean said. “And police in full body gear would surround the patient and they would walk them all the way down the street and through the gates. You couldn’t even drive a car in at the time because the pro-birth people would throw their bodies in front of cars. They would throw their children in front of cars. They would build human chains. It was completely insane.”

On Aug. 25, more than 25,000 abortion opponents converged on Wichita State University’s Cessna Stadium for an impassioned three-and-a-half-hour rally. Despite mounting legal issues for Operation Rescue and community frustration over their tactics, the campaign ended on a high note as local activists vowed to keep up the fight against abortion in Wichita.

As Operation Rescue left town, Tiller and the city’s other abortion providers continued their duties. They had survived the Summer of Mercy.

As the summer wore on, protesters’ confrontational actions increasingly aggravated abortion-rights supporters.

Some, like Carmichael, resented that police had instructed counter-protesters not to demonstrate on clinic property, even as Operation Rescue attempted to block entrances.

“There were some of us who were really appalled that pro-life people were on the private property and pro-choice people were being kept off the property,” Carmichael said. “So there were three or four of us who got together and decided we needed to probably start trying to organize pro-choice people to take an approach which Dr. Tiller’s practice did not at least initially encourage, and that was to call out pro-choice people with signs and tell the police department that we were no longer going to stand across the street.”

Abortion-rights forces were stationed at a house two doors south of Tiller’s clinic at the Pro-Choice Action League headquarters. That’s where Bean, whose mother ran the hotel that accommodated Tiller’s patients, spent much of her summer.

“Back in ’91, it was my grandmother, my mother, [my sister] and myself,” Bean said.

“That’s when my family got started in the whole abortion political — it’s a warfare is what it is really.”

Even at a young age, she understood she was in the middle of something important.

“My mom explained it to us very simple,” Bean said. “She just explained to us that there was a group of people who were saying that women could not choose what they wanted to do with their bodies.”

Most of the time, she had to stay inside the house.

“There was so much violence that went on,” Bean said. “Bomb threats were being made. At one point of time, my sister was in the clinic and there was a threat that was made that there was a bomb inside the clinic, and so the bomb squad had to come out.”

Carmichael and others volunteered to help escort patients in and out of clinics, shielding them from as much intimidation and vitriol as possible. Sometimes, it was Carmichael’s job to distract protesters while a patient was being snuck in through an alternate clinic entrance.

Sometimes they used decoy patients to gauge the opposition’s tactics for the day.

Other times, police had to take over patient escort duties.

“Patients had to park down the street and around the corner (from Tiller’s clinic),” Bean said. “And police in full body gear would surround the patient and they would walk them all the way down the street and through the gates. You couldn’t even drive a car in at the time because the pro-birth people would throw their bodies in front of cars. They would throw their children in front of cars. They would build human chains. It was completely insane.”

On Aug. 25, more than 25,000 abortion opponents converged on Wichita State University’s Cessna Stadium for an impassioned three-and-a-half-hour rally. Despite mounting legal issues for Operation Rescue and community frustration over their tactics, the campaign ended on a high note as local activists vowed to keep up the fight against abortion in Wichita.

As Operation Rescue left town, Tiller and the city’s other abortion providers continued their duties. They had survived the Summer of Mercy.

AFTERWARD

AFTERWARD

AFTERWARD

The spectacle in Wichita created a new blueprint for increasingly disruptive anti-abortion activism around the country.

But abortion-rights supporters were also taking notes.

“We learned a lot from Wichita, and we’re not going to take the pounding they did,” Dana Cloud, chair of the Action For Abortion Rights coalition in Iowa City, said ahead of scheduled protests at the city’s abortion clinic in September 1991.

“What Wichita showed me was that if you let them get arrested, that’s exactly what they want. They come back for more, and they come back for more, and it will never be over,” Cloud said.

“We need to let the pro-choice community defend the clinics — not the police.”

When 75 abortion protesters showed up outside the Iowa City clinic, they were greeted by 300 to 400 abortion-rights demonstrators encircling the facility and chanting “This is not Wichita.”

Back in Wichita though, anti-abortion activists made the most of their energized base.

Mark Gietzen, the new chair of the Sedgwick County Republican Party, recruited abortion opponents to run for precinct committee positions in the August 1992 primary. Of the 308 committee chairmen and women elected, 57 had been arrested for blocking clinic access the previous summer, The Eagle reported.

“Last year, 49 percent of the party’s central committee members were abortion foes. This year, the figure is nearly 83 percent,” Gietzen said at the time.

The spectacle in Wichita created a new blueprint for increasingly disruptive anti-abortion activism around the country.

But abortion-rights supporters were also taking notes.

“We learned a lot from Wichita, and we’re not going to take the pounding they did,” Dana Cloud, chair of the Action For Abortion Rights coalition in Iowa City, said ahead of scheduled protests at the city’s abortion clinic in September 1991.

“What Wichita showed me was that if you let them get arrested, that’s exactly what they want. They come back for more, and they come back for more, and it will never be over,” Cloud said.

“We need to let the pro-choice community defend the clinics — not the police.”

When 75 abortion protesters showed up outside the Iowa City clinic, they were greeted by 300 to 400 abortion-rights demonstrators encircling the facility and chanting “This is not Wichita.”

Back in Wichita though, anti-abortion activists made the most of their energized base.

Mark Gietzen, the new chair of the Sedgwick County Republican Party, recruited abortion opponents to run for precinct committee positions in the August 1992 primary. Of the 308 committee chairmen and women elected, 57 had been arrested for blocking clinic access the previous summer, The Eagle reported.

“Last year, 49 percent of the party’s central committee members were abortion foes. This year, the figure is nearly 83 percent,” Gietzen said at the time.

RESHAPING KANSAS POLITICS

RESHAPING KANSAS POLITICS

RESHAPING KANSAS POLITICS

Energized by the Summer of Mercy, Kansas Republicans took back the House in 1992 to reclaim majorities in both chambers of the state Legislature. Those majorities have held strong for 30 years.

Before the groundswell of anti-abortion activism swept a wave of social conservatives into office, abortion was an issue that Republicans and Democrats in Topeka were seemingly content to avoid.

As Donnally notes in her 2016 essay, “Following the 1974 campaign, state legislators on both sides of the aisle abided by an unwritten agreement to table or kill abortion legislation because if state politicians did not vote on abortion, their positions on abortion would not be easily obtainable by anti-abortion organizations.”

The election of Finney as governor in 1990 served as a warning shot that Kansas politicians’ days of equivocating on abortion were numbered. The Summer of Mercy cemented that political reality, chasing many moderate Republicans out of office.

The changing tides in Kansas also ushered in new representation for social conservatives at the federal level.

Wichita’s longtime Democratic representative in the U.S. House, abortion-rights proponent Dan Glickman, survived a challenge from Republican Eric Yost in 1992. But the nine-term incumbent was ousted in ’94 by Todd Tiahrt, another staunch social conservative.

Tiahrt’s backers mobilized the anti-abortion vote, using an automated dialing system to reach 20,000 to 25,000 potential anti-abortion voters. The phone calls had a simple yet effective message: Dan Glickman supports abortion; Todd Tiahrt is against it. Tiahrt and his successors, Mike Pompeo and Ron Estes, have kept the Wichita congressional seat in Republican hands for 28 years, with Estes winning re-election by more than 27 percentage points in 2020.

“After more than 60 million babies were denied the blessings of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness before they were even born, the disastrous and misguided Roe v. Wade ruling from 1973 has finally been overturned,” Estes said in an official statement after the high court’s decision. “Today’s ruling does not ban abortion, but returns abortion regulation to each state and their democratically elected officials.”

For decades, Kansas has been a key battleground in the clash between abortion rights supporters and abortion opponents. On Tuesday, Kansas voters will decide for themselves if the right to an abortion should be recognized in the state constitution.

Energized by the Summer of Mercy, Kansas Republicans took back the House in 1992 to reclaim majorities in both chambers of the state Legislature. Those majorities have held strong for 30 years.

Before the groundswell of anti-abortion activism swept a wave of social conservatives into office, abortion was an issue that Republicans and Democrats in Topeka were seemingly content to avoid.

As Donnally notes in her 2016 essay, “Following the 1974 campaign, state legislators on both sides of the aisle abided by an unwritten agreement to table or kill abortion legislation because if state politicians did not vote on abortion, their positions on abortion would not be easily obtainable by anti-abortion organizations.”

The election of Finney as governor in 1990 served as a warning shot that Kansas politicians’ days of equivocating on abortion were numbered. The Summer of Mercy cemented that political reality, chasing many moderate Republicans out of office.

The changing tides in Kansas also ushered in new representation for social conservatives at the federal level.

Wichita’s longtime Democratic representative in the U.S. House, abortion-rights proponent Dan Glickman, survived a challenge from Republican Eric Yost in 1992. But the nine-term incumbent was ousted in ’94 by Todd Tiahrt, another staunch social conservative.

Tiahrt’s backers mobilized the anti-abortion vote, using an automated dialing system to reach 20,000 to 25,000 potential anti-abortion voters. The phone calls had a simple yet effective message: Dan Glickman supports abortion; Todd Tiahrt is against it. Tiahrt and his successors, Mike Pompeo and Ron Estes, have kept the Wichita congressional seat in Republican hands for 28 years, with Estes winning re-election by more than 27 percentage points in 2020.

“After more than 60 million babies were denied the blessings of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness before they were even born, the disastrous and misguided Roe v. Wade ruling from 1973 has finally been overturned,” Estes said in an official statement after the high court’s decision. “Today’s ruling does not ban abortion, but returns abortion regulation to each state and their democratically elected officials.”

For decades, Kansas has been a key battleground in the clash between abortion rights supporters and abortion opponents. On Tuesday, Kansas voters will decide for themselves if the right to an abortion should be recognized in the state constitution.